Nothing drags down writing more than spreading good ideas over too many words.

Making keystrokes matter has only grown in importance as communication and the text that powers it become increasingly inseparable. Many tools we rely on each day would be empty shells without the words.

Since everyone in the company is responsible for communicating well, everyone is also responsible for writing well. The importance of this is multiplied when working in a remote culture.

For essays, updates, announcements, emails, and more, here’s an abridged guide to writing with clarity and substance.

Write to express, not to impress

Communication is a mix of vision and conversation. Having noticed something interesting, you now seek to direct the attention of the reader so that they might see it with their own eyes. What you choose to write is for the use of someone else. Always choose selflessly.

The bloated prose found in academia and “legalese” is a reminder of what’s at stake. In The Sense of Style, Harvard linguist Steven Pinker points out that smart people sour their thoughts through attempts to impress others. They spurn simplicity from a desire to prove that they are not bad scientists, lawyers, or academics—in doing so, they unwittingly prove they are bad communicators.

Half the battle with writing is resisting this temptation of the ego. Stick to being straightforward, trust in plain language, and don’t use vocabulary to inflate weak ideas.

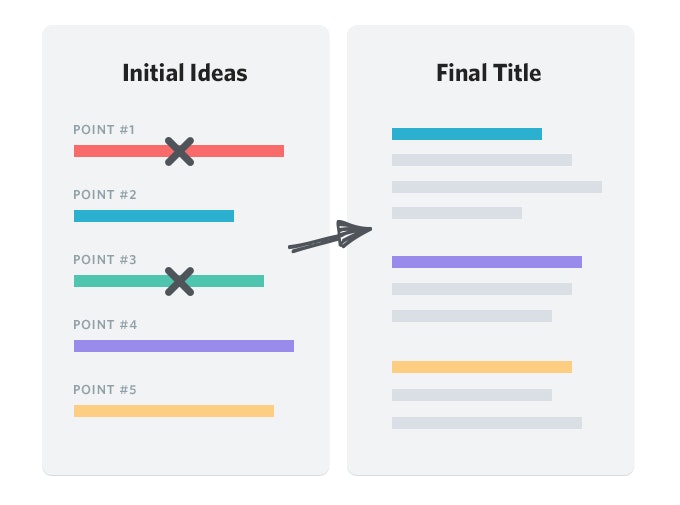

Brainstorm horizontally, revise vertically

What makes for a boring novel is the same as what makes for boring non-fiction: the story grows horizontally instead of vertically.

Writing that is “too wide” tries to explain everything but ends up saying nothing. Part of writing well is deciding where one piece ends and another begins. If you don’t hold the line, you’ll be dragged around by it.

The happy medium? Temporarily lower your standards for the approach. Since expressing ideas helps to form them, you’ll find sitting down to write creates perspectives you never saw coming. That’s a good thing.

From there you’ll have enough to make the hard but necessary decisions about which points to expand and which to save for another day.

People mistakenly expect to hit the bulls-eye on the first pass. Abandon the idea that your first draft should be anything but exploration.

If you don’t subsequently cut out 5, 10, or even 20% of your work in revision, have you really refined anything? Sculptors have marble and writers have ideas; it’s best to start with a block of material and whittle away to what’s needed.

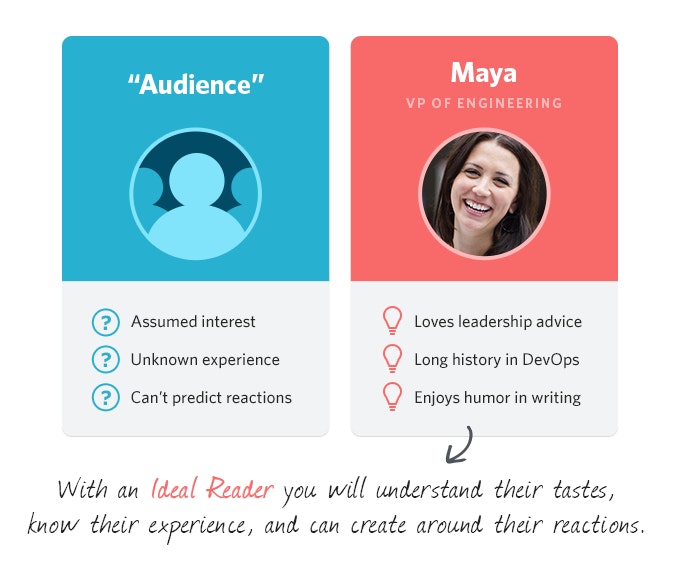

Write for an audience of one

Second to his investing talents, Warren Buffet is known for having a deep-rooted respect for clear communication within companies. His own shareholder letters are so well written that they are often considered the gold standard for the medium.

When introducing the SEC’s official Plain English Handbook, Buffet chose to offer up his “unoriginal but useful tip” to act as if you are communicating to a single person.

Buffet usually writes with one of his sisters in mind, noting that while highly intelligent, she has little experience with investing. If he sees a passage that will confuse her, he knows he hasn’t written it properly.

Stephen King suggests the same approach in his book On Writing. Picturing his wife combing through each line, he found himself able to create around reactions. Where would she become bored, laugh, be surprised, or skim until the story picked up? He knew the answer because he knew the reader.

Writing to delight a single person whose tastes you understand is practical; writing to appease a faceless audience whose tastes you will never know is impossible.

No need to worry. Picking the right person and conveying your message with care will make what is fascinating to one enjoyable for many.

Relentlessly re-earn attention

David Ogilvy famously said that once the advertising headline is written, you’ve spent eighty cents of your dollar. You must open with gusto. Captivating titles and hooks won’t soon lose their ability to move mountains (and millions).

But great writing doesn’t just earn attention; it continually re-earns it. Lose people in the middle and the complete story won’t be told. No matter how grand a first impression you make, if it doesn’t sustain, that counts as a loss.

Here are a few ways to catch and keep readers until the final line:

Never bury the lede. Make the value proposition clear from the outset in everything you write. If your objective and the reader’s incentive are not obvious within the first few paragraphs, re-write them.

Dress your thoughts well. One of my dad’s favorite expressions is, “Exercise improves everything.” It captures the life-changing transformation that occurred when he took up bodybuilding. “Working out is good for you” imitates the brevity but loses the punch. Often a re-framing is all that’s needed to make an accurate statement a timeless one.

Avoid circular and repeated points. “In other words,” you should just use those other words. Insight is memorable when it can be embraced directly—don’t pad it with “essentially,” “basically,” or “in other words.” Use the right words the first time.

Structure cannot be an afterthought. The best writing is that which pleases at a glance but further rewards careful study. How you structure a piece matters, as do the words that create the structure. You’ve made a mistake when you start using sub-headings like “In Conclusion.” There are far more compelling ways to communicate.

Meandering endings will dilute your message. It’s best to approach them quickly. Paul Graham handles this one with grace, so I’ll let him bring it home: “Learn to recognize the approach of an ending, and when one appears, grab it.”