As your company grows, it’s important to evolve your organizational structure just as you would your product.

If product-market fit is like oxygen for a startup, then your company’s structure determines how fast you can run. A lack of structure can lead to confusion about who is responsible for what, but too much structure can create bureaucratic bedlam and misaligned incentives.

One way dysfunction can rear its ugly head is when creative people are forced onto a “management” track to make the career progress they deserve. It’s common (and often unintentional) to over-privilege managers as you add more hierarchy.

Why does this happen? Because leading people scales better than creativity. It’s logical to assume that an employee leading 10 people adds greater value to the company than the best single performer on that team. That’s why great performers often end up in management, even when they aren’t excited about pursuing it.

It’s a bit like telling Steph Curry, “Nice job hitting 402 three-pointers this season. It looks like you’re ready to put on this suit and stand on the sidelines.”

Since “manager” and “individual contributor” both have a bit of stigma attached, we refer to these roles as “coaches” and “players” at Help Scout. There are exceptions, but most people discover their skills are largely in one role or the other.

Discover the most important lessons we've learned running a fully remote company for 9+ years.

Benefits of player and coach roles

These words reinforce important associations for us culturally. First, when you think of professional sports, players come first. Fans wear player jerseys for a reason.

Players (designers, engineers, writers) are the heart and soul of Help Scout. They embody what we want to be about. A coach’s role is to serve players, to help them seek excellence, and to ensure their team is greater than the sum of its parts. This speaks to the servant leadership we want from our coaches. There’s no room for “command and control” leaders in our company.

Coaches and players are also remarkably title-free. While external/LinkedIn titles need to exist in some way, I love keeping things simple internally. Titles have a way of giving a player or coach some sort of implied power or authority. I’ve seen organizations use a “title bump” to promote someone without actually giving that person a raise. That seems disingenuous, so we try to limit the use of titles internally as much as possible.

Players play; coaches coach

On a small team, even within a larger company, it’s often necessary for people to take on the role of a player-coach. Being a player-coach isn’t a bad thing, but we’ve found it’s usually suboptimal; context-switching between roles can be deeply distracting.

Once a team reaches six to eight people, we try to have any player-coaches choose the path they are most excited about, then hire for the role they leave. They don’t have to take a salary cut, and now they’re able to focus on a single role to be at their best.

Keeping these roles as separate as possible helps reduce excessive hierarchy. When coaches are in a dedicated role, they can serve anywhere from 8 to 12 people. Currently we have a 22-person engineering team and only two coaches. It feels flat, and I love that I can work directly with our coaches to get things done. With a hybrid consortium of coaches and player-coaches, you could end up having six people with direct reports on the same 22-person team, which is a telltale sign of superfluous management overhead.

While there will always be exceptions, we always try to stick with the distinction that “players play; coaches coach.”

Two types of leadership

In every company, there are two distinct types of leadership: people leadership and domain leadership.

Career ladders should reward leadership, but that shouldn’t be defined as how many direct reports someone has. If a designer on your team contributes to open source projects, writes and/or speaks regularly, and most importantly, raises the quality of work done by the entire team, they’re exemplifying domain leadership. The last thing we’d want to do is force the designer to become a manager, because they clearly have valuable skills as a maker.

When players lead, they should be able to climb the career ladder just like anyone else.

Requiring great players to manage people in order to make career progress puts both groups on the road to dysfunction, because those players will likely end up in less valuable roles.

How I learned the hard way

Denny Swindle is CTO and one of my co-founders at Help Scout. He’s one of the smartest and most creative engineers I’ve ever met, and he means a lot to our business. As our company grew early on, we did the natural thing and put Denny in charge of all the engineers we hired. Before we knew it, he was a coach.

Denny would tell you he wasn’t at his best as a coach. When he had to spend the bulk of his time managing projects and people, he wasn’t able to be the technical architect we all depend on, which created tension in our relationship. Thanks to some help from an outside advisor, we quickly realized that Denny’s passions and skills were most aligned with being a player. Leading people wasn’t the best or most desirable use of his time, but as a domain leader, he remains critical to our business.

We went on to hire a great VP of Engineering named Chris Brookins to lead the people on our engineering team, and in Chris, we found someone who complemented Denny in every way and freed him up to be at his best as a player.

Finding alignment on compensation

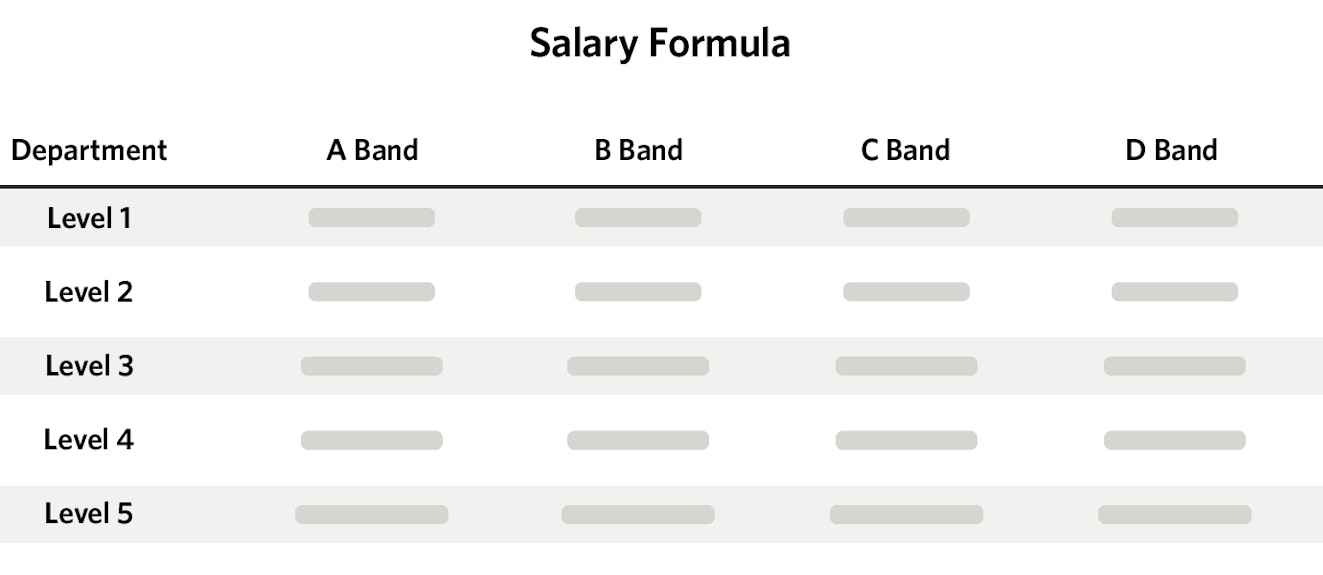

The player/coach system works best when everyone is climbing the same career and compensation ladder. At Help Scout our ladder takes the form of a salary formula. While individual salaries remain private, the formula and all the numbers are transparent within the company.

Players and coaches are measured on the same scale, which considers three factors:

Experience: A combination of excellence in your craft, your velocity, and your ability to contribute new ideas and best practices.

Impact: Your effect on everyday team productivity, on your peers, and on the business as a whole.

Leadership: Your level of independence, influence, and how you use your skills to change the course of both your team and the business at large.

I’ve seen players and coaches demonstrate these things at high levels. It may look different, but the business value created is the same — therefore the compensation and career path should look the same as well.

We check in on career goals every six months. There are times when a player expresses desire to become a coach someday, and we want to give our support. However, since we try to have a player/coach ratio of about 7:1, there are also times when that opportunity lies outside of Help Scout. That’s OK too, and we’d prefer to have that sort of discussion out in the open.

Isn’t there still a ceiling for players?

If the ladder is truly based on the three factors above, there are some cases where the career ceiling can be lower for a player, but the truth is that every person in your company has some form of ceiling (CEOs included). We just like for the ceiling to be a place that pays you above market salary and empowers you to do work you are excited about every day.

You have to give players a path

Everyone at your company depends on significant opportunities for career progress.

Without career growth, you can’t expect to keep talented people in any role.

In some companies, the greatest players are given no choice but to set their sights on some VP-level job, where they have to abandon the work they love in order to manage people. I’m advocating for another path that gives them the same sense of purpose and career progress but also aligns with their skills and passions. It doesn’t form naturally, so as a leader, you must create that path for them.