How a company manages a tough crisis often gives customers a far more honest look at how they are run than any meticulously crafted press release could ever offer.

Perhaps it’s because we all inherently know that it’s far easier to “do the right thing” when the chips are up. When the ship’s sinking, though, things can get ugly.

That raises an important question: what is the right way to handle an internal company crisis? Of course, situations differ, but surely there are some guidelines on what businesses should do when they’ve dropped the ball, right?

Below, we’ll look at some research from Stanford on how you should approach your mistakes, as well as examine some important case studies on companies that did things right and others that did things very, very wrong.

The Case for Owning Your Mistakes

The prevailing opinion about “what to do” during a crisis is undoubtedly that the company should own up to what happened and be transparent about the entire situation—at least that’s what most customers would tell you.

Questions aside about whether or not this is the right thing to do, one has to wonder if customers and investors actually reward this behavior in reality.

The impartial nature of research often leads to answers we don’t want to hear, but fortunately, this time good intentions align with positive business results. According to a study from Stanford, companies who admitted to their missteps were often rewarded with higher future stock prices.

Now, this study was quite biased towards the corporate world and to stock evaluations, but the lessons from the research are quite applicable to small businesses.

Executives who blame external, uncontrollable causes for problems may seem less trustworthy. If an executive takes responsibility for negative outcomes, says Tiedens, "the reader thinks, 'Oh, this company knows what it's doing, they're in control of it, they can change it.'"

In other words, blaming external situations (even if true) often created a sense that the company was unable to fix their own problems or were simply looking for an “out.”

Conversely, owning up to poor performance or a specific shortcoming instilled the sense that the company had a tight grip on the reins and were more likely to rebound from the situation since they had already identified the problem and accepted responsibility.

Putting Theory to Practice

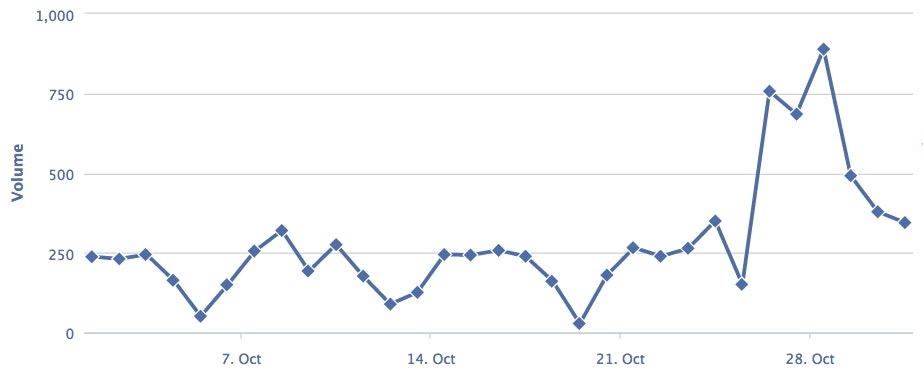

Recently, our friends at Buffer experienced what was undoubtedly one of the scariest moments at the company since its inception.

How they handled this crisis, however, serves as an excellent case study for the research above, and makes a strong case for the positive impact of transparency.

What went down:

On October 28th, the app suffered a security breach that resulted in thousands of accounts posting spam messages to Facebook. The stage was set for a monumental meltdown, but the way their team handled the situation was so exceptional that a majority of their users responded with well wishes and sincere thanks for the honesty and professionalism:

Hard to ask for a better response than that, so what did the Buffer team do right?

1. Own the mistake

In some situations, “blame” begins to get passed around like a hot potato. During freak accidents or problems caused by outsiders (such as in this situation), some companies look for a way to shield themselves from customer frustration. I’ve mentioned before that this is almost always the wrong course of action—saying “I’m sorry” is more about being apologetic that the customer’s experience wasn’t the best it could be, and that’s always worth conveying.

Buffer eschewed the blame game and simply owned up to the problem directly. The situation didn’t become about finger-pointing at some anonymous hackers that their customers couldn't care less about. Instead, they immediately took to every communication channel they had, apologized for the inconvenience, and explained what was to be done as soon as they got a handle on the situation.

Hi all. So sorry, it looks like we've been compromised. Temporarily pausing all posts as we investigate. We'll update ASAP.

— Buffer (@buffer) October 26, 2013

2. Frequent, transparent updates

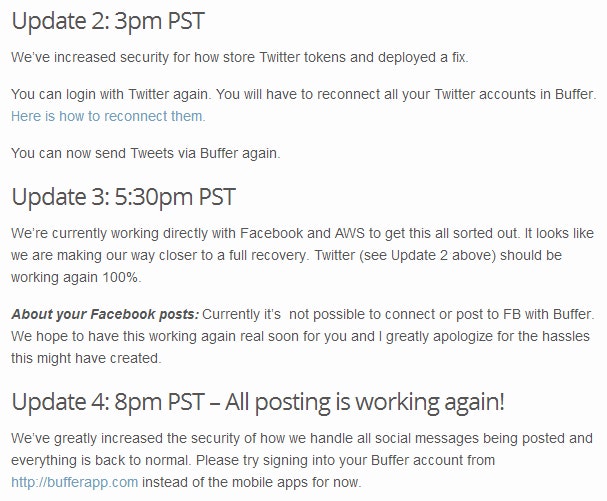

In a shining example of “defaulting to transparency,” Buffer chose to publish a blog post which was updated ten times with the ongoing status of the hack and their efforts to make things right. Being in the dark about a situation like this is perhaps the most frustrating part for customers, and these updates went a long way in eliminating that problem.

Just as important, putting the situation and current status out there for all to see served as proof positive that the team was taking control of the situation. We know from the study above that this should be to the advantage of the company in question, and given the ample coverage they received for this action (99.9% of it positive), it’s safe to say that it was definitely the right move.

3. All-hands response

Perhaps the most interesting part of this case study is how Buffer utilized the practice of Whole Company Support to deal with the influx of communication from customers. As Chief Happiness Officer Carolyn Kopprasch recently revealed, the influx of emails the Buffer team received during the hack was staggering:

Not exactly ideal. However, with all Buffer employees having at least some experience handling support, an all-hands situation became possible. Having the development or marketing teams sit back and watch the customer support team drown in emails because “that isn’t my job” is a surefire way for a small company to get caught with their pants down. If Jeff Bezos can spare time to work in an Amazon call center, can’t your entire team get acquainted with supporting customers?

Five Examples of Doing it Wrong

The incredibly positive reaction that Buffer received in handling this crisis is perhaps quite telling of what people generally expect from companies during a crisis (i.e., they don’t expect much and were pleasantly surprised).

There are, however, quite a few lessons that we can learn from companies who have dropped the ball during a crisis. We all make mistakes, and if nothing else, learning from others’ foul-ups makes us better prepared to avoid a repeat scenario.

1. Going Dark During a Crisis

The antithesis to the great example Buffer set in responding openly and immediately is the nearly week-long response time of Sony Entertainment during the notorious 2011 PlayStation Network attack. If you haven’t heard of the story, you should understand that this was one of the largest data security breaches of all time, with over 77 million customers affected.

People were outraged—if Sony deemed the attack dangerous enough to shut down the entire PlayStation Network, why did it take them days to let customers know that their personal information (and even credit card data) could potentially be stolen? Sony is a very large company, but surely a week wasn’t needed to candidly tell customers what was going on, what they should do to protect themselves, and what Sony planned to do to make things right.

2. When Employees Go Rogue

The nature of a crisis is that it is usually unforeseen, but as the following example shows, simple steps can often be taken to ensure that important company accounts—especially public social media profiles—will be secured, even if an employee decides to go rogue.

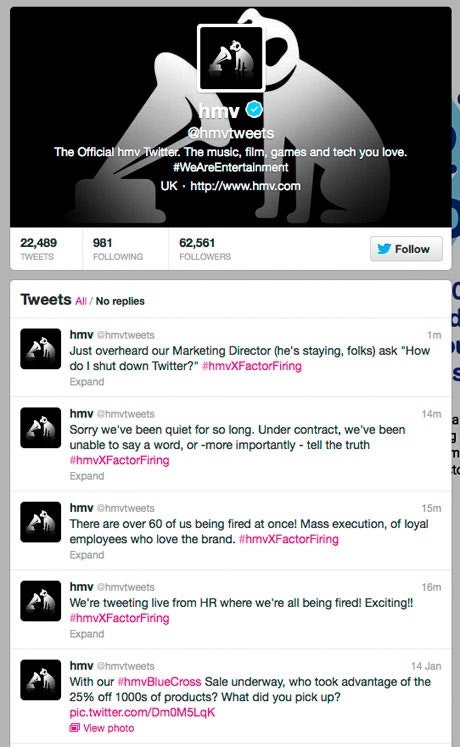

It’s hard to say whether or not HMV (a British entertainment company) “deserved” to have it’s business aired out on Twitter, but when the company recently let nearly 60 employees go, their Twitter account was taken over by one of the disgruntled employees and multiple messages about the “mass execution” were shared on the company account.

Back when we discussed the power of virtual teams, I noted that trust was a big part of making a team work. That doesn’t mean that systems shouldn’t be in place to ensure that important company assets can be protected from actions from individuals. Admittedly, this is one of the most difficult forms of crisis to plan for, but take notes on what can go wrong from HMV when angry employees have access to important communication channels.

3. Keeping Your Cards Too Close

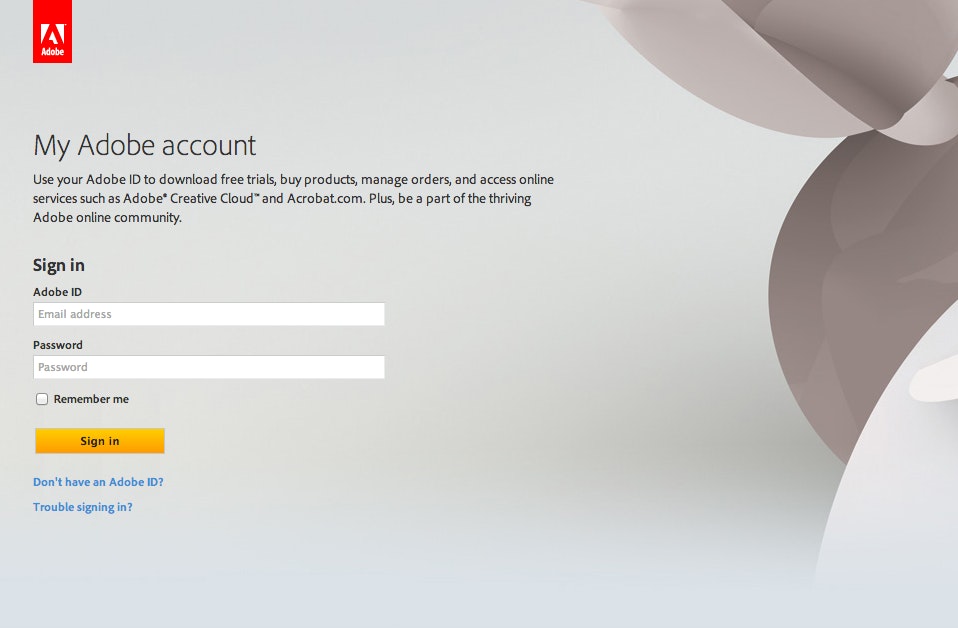

Another recent hack, this time, the stage light glares at Adobe, who recently had their database of over 150 million users leaked this past October.

What’s shocking is that the coverage of the story often contains statements like this:

"Much of what we're learning about the breach has come from independent researchers not affiliated with Adobe."

While it’s easy to understand some need for privacy and secrecy with a breach of this size, responses through snail mail and email have been slow (many, including myself, have received no communication at all), and there isn’t a single notice of the incident on any of Adobe’s login pages:

It’s very possible that Adobe still knows little about what happened, but the silence after this attack was pretty deafening to many users and should have been handled with more care by Adobe.

4. Taking Things Personally

Better to remain silent and be thought a fool than to speak and remove all doubt.

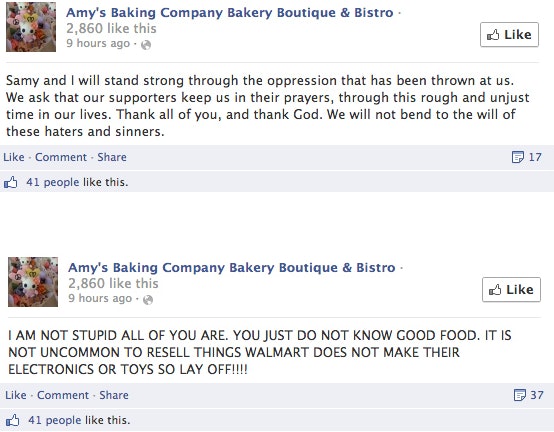

These are words of wisdom that the folks at Amy’s Baking Company could have used earlier this year. After appearing on Gordon Ramsay’s Kitchen Nightmares (resulting in Gordon walking out), you would think that Amy’s would launch a full scale “redemption” campaign in order to save face with customers.

Instead, the owner took the continuing online criticism very personally, and opted for a world-class meltdown. It takes a thick skin to run your own business, and although it’s perfectly natural for criticism to sometimes get to you, the worst thing you can do is take to you company social media accounts to put the “haters” in their place.

The backlash against the little store was far worse after the above stunts on social media than it ever was due to the show. Wharton professor Jonah Berger says negative publicity is like playing Russian roulette, so unless Amy’s Baking Company plans to take the “reality show” idea all the way, it’s safe to say that this example of bad press definitely blew up in the company’s face.

5. Letting Problems Fester

When employees are encouraged (often subtly, through company policies) to do the bare minimum, that is what they will do. Companies that don’t reward outside-the-box thinking to help a customer are bound to run into something similar to this next disaster. After a Verizon Wireless customer’s dad died, the company continued to charge the account, and since no leeway was given to employees to fix things, they simply shielded themselves behind the “I’m not able to do that” script.

It’s disgusting to think that this could happen, but this nonsense went on for four months, even after the customer sent in her father’s death certificate. It’s hard for me to imagine an instance where Verizon’s support team could do a worse job than they did here. Reportedly, one of the staff told the customer “Well, there's nothing else I can do for you,” before laughing and hanging up the phone!

Fortunately, things were eventually settled for the customer, but not before the press lambasted Verizon’s customer service, an outcome they certainly deserved.