Recently, I had a really interesting conversation with my dad, a captain on our local police force, about "the stats."

Apparently everything I watched in The Wire is true, and police departments really do get hung up on delivering the stats required, even if they don't result in real improvement in the community.

This is what my dad was worried about. He was working with a police force veteran and consultant on the issue in order to come up with ways in which they could effectively communicate to both the administration and the police officers that more arrests don't necessarily mean a safer neighborhood.

It was a real world example of a false proxy. Some things end up becoming the focal point simply because they are easy to measure, and they seem like the logical metric to manage.

But tunnel vision can occur when this happens. Cops forget about big busts and focus on the arrests they can get, if the required metric becomes "X arrests per quarter."

Does the stat game interfere with businesses growth, too? It certainly seems like it, especially if you are looking to "hack" a specific metric up and to the right.

Today I thought we'd explore how metrics can intertwine with big picture objectives like creating a delightful customer experience. Growth hacking, the term we all have come to know in the past few years, has made this an issue that needs discussing.

Starting with a "neutral+" experience

Juking the stats at the expense of the customer experience will sabotage long term growth in any business.

When a new strategy is about to be tested, the bar must be set at a “neutral” experience for customers. It must not negatively impact their experience with your brand.

This doesn't mean you need to be a passive entity that never asks for anything. You'd be surprised to learn what I've found (through data, not opinion) to be neutral. A single casual pop-up is actually neutral, despite what armchair marketers might tell you.

Spamming your users? That isn't neutral, and surprise—it'll come back to bite you.

Starting with a neutral+ experience threshold means caring about your users:

But as 'Growth Hacking' has gotten more competitive and difficult, it has started to move into “Growth Hawking,” a disease that crushed search engine optimization and later social media marketing, and is fast working its horrible magic on app store optimization and all the other optimizations that are soon to come.

The conversation about the importance of delighting customers is not quite complete bullshit. Yet.

— Micah Baldwin

When you can set the bar to at least neutral, "hacking" your growth doesn't become such a liability.

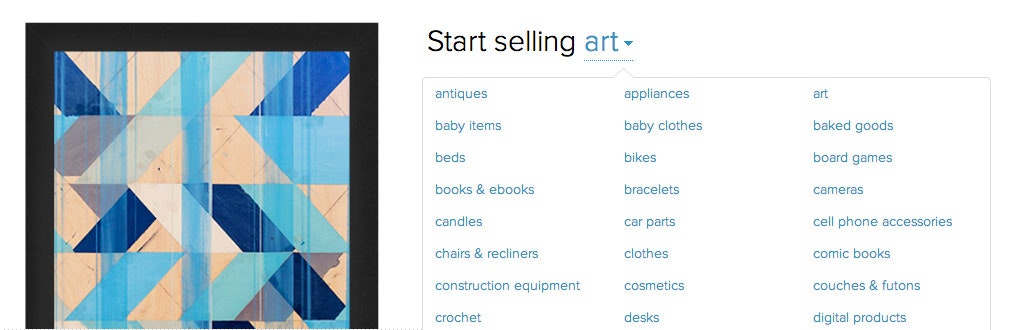

Let me show you an example I loved, coming from my friends at Shopify. Since SEO now apparently falls under the growth hack umbrella, I was delighted to find out how effectively their team was using the Shopify “sell” page:

Surely, if I'm interested in opening an online store, I'll find my desired category here. Let's say it's candles. I click, and I'm greeted with a page explaining how Shopify can help me sell candles online. The thing is, if I clicked on the “guitars” tab, I'd be greeted with a very similar page.

So why do this?

That's right, each page has the title tags optimized for whatever item you pick. Clicking "candles" generates a semi-customized page (easy to scale) that is built for the term "Sell candles online."

This is a fantastic way to "hack" for multiple search terms, and it's customer experience neutral. It doesn't interfere with my use of Shopify or my research into their product, and it certainly is fair game for people looking for those search results. (Shopify is a great piece of ecommerce software!)

But a neutral experience is just the beginning—it’s the bare bones of any new growth hack. When you can create a delightful experience as an added benefit, you've really found a winning situation.

However, we also need to remember there’s a dark side to growth hacking: When you throw experience to the wind, that’s when things fall apart.

When growth hacking goes wrong

Gaming the system is never the goal. The goal is the goal.

Why the emphasis on delight, or at the very least, a neutral experience?

If you're going to be aggressive with your growth, you should know this: growth hacking can end up being marketing on steroids—that is, it can create artificial growth that has disastrous effects for the long term health of your business.

No wonder, then, that we find articles on the dark side of growth hacking like this one, detailing case studies that nobody wants to talk about:

The problem for Viddy was that Instagram had built its own network, its own social graph, separate from Facebook or Twitter. Viddy was part of a group of apps that rocketed to popularity thanks to viral distribution on Facebook. When Open Graph debuted, Facebook wanted to prove its worth to app developers, and opened the floodgates, allowing apps to artificially inflate their numbers.

“This stuff will shrivel your nuts and give you zits all over,” Lawrence Lenihan, managing director at FirstMark Capital told me at the time. “It doesn’t help with building a sustainable, long term business. It’s about getting big fast so you can flip the company…”

Source: Viddy CEO out as Vine steals the video sharing spotlight

Viddy subsequently plummeted from 30 million monthly uniques down to just 4 million.

I guess that's what happens when someone decides that total accounts created is the metric they want measured, at the expense of delighting users.

In Silicon Valley, where some startups play out like an episode of Who's Line Is It Anyway?—the show where everything's made up and the revenue doesn't matter—maybe it's desirable to inflate your growth so you can leave someone else holding the bag.

Real companies who are looking to last and who provide real value to their customers won't do this. It's fine to be creative. It's desirable to be innovative. It's even recommended that you sometimes be aggressive with your marketing—but growth hacking promotes gamed numbers over user delight. It is a bias built into the term itself.

Is Growth Hacking™ just a branding play?

When you get a cut on your finger, what do you need to grab? A band-aid?

Band Aid™ brand certainly wants you to think so, but what you actually need is a bandage. That's the trademark effect in action.

Business terms have a weird way of taking over our diction, whether they’re orchestrated or naturally occurring. In the startup community, they seem to catch on whenever an older phrase doesn't fit with the trendy new ideal.

I'm not talking about the ridiculous use of “ninjas” and “rockstars”—I'm referring to job titles and business activities that now require a thesaurus to figure out what they are:

Customer service rep became "happiness hero" or "support champion" because people didn't like being associated with overseas call centers (we use these, too—guilty as charged).

Internet marketing became "inbound marketing" because online marketers didn't like being associated with get rich quick peddlers. (Also, because HubSpot pushed it�—hard.)

Small businesses became “startups”, a term that is forever misused, often for businesses who are far beyond legitimate startup territory.

Which brings us to Growth Hacking™—tech geeks, for some reason, see marketing as a dirty word. They sometimes brag about hiring for product only. But growth, that sounds nicer, and hacking . . . ooh, the engineer in me feels all warm and fuzzy inside!

Don't get me wrong: Sean Ellis—who coined the phrase—is an incredibly smart marketer and someone I look up to. But growth hacking is little more than a branding play.

Ellis would prefer you call it growth hacking in the same way Band-Aid brand wants you to call bandages “band-aids” (funny, coining a term can be considered great marketing).

Believe me, I've tried to see things the other way, but in taking the explanation of growth hacking from the source himself, I see a lot of leaps in logic that try to explain away the correct use of innovative marketing in favor of a new term.

The majority of traditional marketers like to say “that’s exactly what I’ve been doing – that’s just marketing.” But rarely do I see any of them having a track record of building truly innovative, rule changing programs for driving growth. Most just don’t have the need or motivation to change the rules or innovate new channels."— Sean Ellis

This sentiment is fantastic! We'll explore it more later, but looking past the term, it's hard to deny that this is simply a call for innovative marketing.

One of the most popular slideshows on growth hacking lists Dropbox as a top example; a referral program is a growth hack now? Twitter's suggested users are also mentioned; sounds a lot like onboarding to me.

Lastly, highly popular articles on the daily schedule of a growth hacker read like what every marketer at a startup should have been doing since 5 years ago.

Perhaps the most compelling description comes from Andrew Chen. Still, Chen merely points out a technical side to marketing, such as Airbnb's "hack" to integrate with Craigslist (the best example I've heard of yet).

It's a far better argument than calling basic conversion rate optimization a growth hack, but it's still just a technical side to marketing. The fact that it's only an option for an internet company seems to indicate that "internet marketing" would be an appropriate term, would it not?

Either way, why bother with this lengthy discussion of the term itself?

Words and, more importantly, labels, matter. How you see yourself affects how you behave, and when you are calling yourself a growth hacker, there are some interesting implications.

The dangers of business euphemisms

Funny that George Carlin's take on euphemisms seems oddly relevant in this business context.

When one defines their activity as growth hacking, a certain perspective begins to form, and how this perspective plays out is very important.

Perhaps this person labeled growth hacker will thrive under a role that prides itself in innovation. Perhaps the label will encourage them to really think outside of the box in both growing the business and in delighting new users.

But perhaps not.

Perhaps being labeled a growth hacker encourages this person to seek ways to game the numbers. They find a metric that needs to go up and to the right, and they start losing sight of the big picture. Intercom rightly says, "If it's important, don't hack it," but this label implicitly encourages folks to do so.

Tunnel vision has helped to triple sign-ups, but nobody ends up actually paying.

Assigning roles and labels matters. Language matters. Calling yourself a growth hacker is more than a title change—it can result in a change of your state of mind, depending on how you interpret what the role requires of you.

So tread with caution.

Despite my opinion, and the friendly jabs I've taken towards a term I believe is just unnecessary, I don't actually care what you call yourself.

I care that you are delighting customers, helping them see the value in your product, and helping customers enjoy or succeed with the use of your product (like a marketer is supposed to do).

Call yourself what you'd like, just don't let growth hacking ruin the customer experience.